Lines On The Water

‘It’s the water, stupid’ – the big challenge for any new government

‘When the world ends, someone will have daubed on a wall somewhere “It was the water, stupid” in a parody of Bill Clinton’s famous campaign reminder to his team to remain focused on what matters most.

As an angler I’ve lived all my life in, on or beside water. The rivers, oceans, lakes and ponds that have been my obsession for more than half a century are dying before our eyes. Either sucked dry by our relentless demand for more of this most precious natural resource or engulfed in a tidal wave of sewage and slurry, often both. Short sighted stupidity has been the hallmark of national water policy since before the Industrial Revolution. The current situation is little short of alarming:

- Only 14% of our water bodies are now in good ecological condition.

- In 2023 a total of 579,581 sewage spills recorded from storm overflows in England and Wales for a total duration of 4.6 million hours.

- Wastewater infrastructure replacement rate for pipes and main sewers is running at 0.05% of the network per annum – 10 times longer than the European average – meaning sewers with a 100-year life expectancy are meant to last for 2,000 years.

- Environment Agency numbers show that in just the last year at least 120,000 fish were killed in sewage-related pollution incidents – the true figure will likely have been much higher.

- The Atlantic salmon is now officially classified as an endangered species in the UK.

With a general election just a few weeks away the condition of our rivers and waterways is higher up the political agenda than it has ever been. This follows years of relentless pressure from energised campaign groups such as Surfers Against Sewage, Angling Trust & Fish Legal, The Rivers Trust, Wildfish, River Action and many angling and local groups across the country, ably supported by celebrity angling activists like Feargal Sharkey, James Murray and Paul Whitehouse. Whilst it’s pleasing for campaigners like me to see our chosen cause front and centre of political debate, what is less encouraging is the failure of all political parties to acknowledge the depth and scale of the problem or to apply any serious thinking as to what needs to be done.

Last year over 579,000 sewage spills were recorded from storm overflows in England and Wales

Soundbites won’t fix our rivers and seas, but here’s 12 things that will make a difference if we elect a government with the guts to do what’s necessary.

1) Recognise that there is no such thing as cheap water

My local water company, Thames Water, provides my three-bedroomed, semi-detached house in Reading with clean, drinkable water for a little over £1 a day. Absurdly, I can also use this heavily-treated liquid to water my garden, wash my car, and to flush my toilet. Speaking of which, my bodily waste is also taken away and allegedly treated before being discharged as effluent back into the same river system from which it came. That same pound will scarcely buy a bottle of water in a supermarket, or a glass of the stuff with added bubbles in a restaurant, yet people regularly hand over wads of cash without a second thought for both, even though what comes out of their taps costs almost nothing.

Water for almost nothing is no basis on which to build public policy about a basic resource on which all life depends, human, animal, bird or fish. Water needs to become as political in Britain as it is in other countries where living conditions are far harsher.

Look behind many of the conflicts and tensions in the world today and what do you find? Conflict over water. Too much of it, causing sea levels to rise as we fail to heed the warnings of climate change and more of the earth’s surface becomes uninhabitable. Too little of it, as warming temperatures turn once productive regions into searing dust bowls, causing millions of our fellow human beings to begin a giant migration in search of livable land.

2) Tackle the investment backlog

In 2021, my organisation jointly published a report looking at the sheer scale of the investment backlog facing the water industry. Called ‘Time to Fix the Broken Water Sector’, it exposed the ticking timebomb at the heart of the UK’s wastewater infrastructure that threatens the health of almost every river and stream in the land. The key finding were:

- A £10 billion investment funding gap over the last 10 years.

- The declining condition of rivers and streams due to increased sewage spills every year.

- The absurd expectation of a 2,000-year lifetime for sewage pipes and other infrastructure.

- Failure to build any new reservoirs in the south-east since 1976 despite a 3 million population increase and huge projected growth in house building.

- Lack of investment in water supply has seen excessive groundwater abstraction drying up some chalk streams altogether and damaging many other rivers.

- The impossibility of delivering commitments in the Government’s own 25 Year Environment Plan and our legal obligation under the Water Framework Directive.

- Failure of both the Government and OFWAT to heed the promises in the 2011 water white paper, or indeed the warnings from the National Infrastructure Commission and the National Audit Office, about the pressing need for investment in water and sewerage systems to address the challenges of climate change and population growth.

- The prospect of severe drought events causing parts of southern England to run out of water within 20 years.

- The consequences of failing to invest in water infrastructure that will cost more in the long term – £40 billion versus £21 billion, and thousands of jobs.

Much of this sorry state was triggered by the politicians’ wish to kick the can down the road rather than face up to the looming water crisis. And behind all of this has been the thoroughly useless regulator OFWAT whose former Chief Executive and previous water industry fat cat, Johnson Cox, promised in 2017 – ‘a decade of declining water bills.’ He did this at a time when OFWAT had neither the engineering nor environmental expertise to make these judgements, unless, of course, you didn’t give a fig for the environmental consequences. As a result, the price limits were set so low that under-investment was inevitable, making a bad situation worse.

Cover of the ‘Time to Fix the Broken Water Sector’ document – download the full report

3) Abolish OFWAT

It is patently absurd to have two regulators allegedly overseeing the water industry. You can’t separate the consequences of economic regulation (OFWAT) from the impacts on the water environment (Environment Agency). The consequences of the OFWAT investment roadblock are plain to see. Here are a few examples:

- OFWAT directly cut planned investment in PR19 (between 2020-24) by £6.7 billion (or £1.34bn each year). They even boasted about the size of investment they had prohibited water companies from making.

- OFWAT held down bills below inflation for over a decade, removing around £11 billion from investment that should have been ring-fenced for improvements. Allowing bills to increase with inflation over the last decade would have provided more for investment, which could have been ring-fenced for the most urgent projects. This would have been the equivalent of sufficient funding for up to half a dozen reservoirs or meeting overflow targets five years earlier.

- OFWAT decisions overturned. Four companies successfully appealed their PR19 decisions to the Competitions and Markets Authority (CMA) who ruled as follows to:

- Restore £7 million for Yorkshire Water to cut overflow spills, deliver wastewater upgrades, and the protection of tens of thousands of properties in Hull against flooding.

- Restore £18.3 million for Northumbrian Water to prevent 365,000 properties in Essex being cut off for a potentially extended period.

- Protect £40 million investment in strategic water interconnection by Anglian Water, rejecting Ofwat’s decision that would have reduced the capacity of the interconnection pipes.

- Restore £ 5 million for Anglian to increase its sludge capacity to minimise the operational resilience risk around their ability to deal with increased volumes.

OFWAT has clearly shown not to be fit for purpose. It should be abolished in favour of a publicly accountable single water regulator alongside a complete reform of the management and rebuilding of the UK’s water resources to deliver clean and plentiful water and wastewater infrastructure fit to meet the challenges of climate change and a growing population, without further damaging the environment.

4) Accept that underfunding leads to failure and underperformance

OFWAT’s rejection of necessary investment has directly caused problems. For example:

- The whole industry was denied sufficient funding for leakage improvements over more than a decade.

- They refused almost all of five English and Welsh companies’ climate resilience proposals to fund wastewater capacity upgrades, cutting the budget from £403 million to £16.4 million. This stopped £387 million of investment that would have allowed a half-decade head start on the storm overflows programme while also reducing sewer flooding.

Given the scale of both the environmental and economic challenge posed by a failing water sector with a crumbling infrastructure, the next government has little choice but to introduce primary legislation to abolish the two regulator model and overhaul the entire regulatory oversight of the industry to put environmental needs front and centre in a complete sector reset.

5) End the casino economy in the water industry

When water was privatised in 1989, the new companies were able to acquire public assets that were completely debt free. Thirty-five years later, companies like Thames Water are now a staggering £15 billion in debt and teetering on the brink of bankruptcy. A succession of private owners levered this debt mountain to strip out more than £7 billion in dividends to shareholders whilst paying eye-watering bonuses to top executives as a perverse reward for presiding over operational failure and turning a blind eye to financial sharp practice. Vampire owners like Macquarie should never have been allowed to mortgage their company’s balance sheets to fund excessive dividends. OFWAT could and should have prevented it.

Every piece of this scandal took place right under the nose of OFWAT, whose senior directors see no contradiction in taking highly paid jobs in the same companies they are supposed to be regulating only the month before.

The next government needs a new Water Industry Act to either create entirely new community interest entities to operate the water infrastructure or, at the very least, to correct the gaping loopholes in the current legislation that allow public assets and vital public resource to be traded like Bitcoin irrespective of the looming threats to both the economy and the environment.

6) Give the Environment Agency the power and the resources to do its job

The EA has been systematically hollowed out by a 57% cutback in its resources since 2010 turning from the bulldog it should be into the ineffective lapdog it’s now become. Enforcement rarely occurs and when it does it can take years to bring polluters to court. Only a minority of reported fish kills will even trigger a visit from Agency staff who are now simply spread too thin to be effective.

The organisation has suffered from poor leadership and is massively risk averse at a time when environmental stakeholders and the public at large are looking to it to take tough action in defence of our rivers and waterways. The Environment Agency is now under new leadership. The next government must give them the resources to do the job, and make it clear it must hold polluters to account, and ensure the protecting the environment is its first, last, and only priority.

Only a minority of reported fish kills trigger a visit from Environment Agency staff

7) Treat water as national infrastructure priority

Part of any new deal for water must involve getting serious about planning and building control. It must treat water as a national infrastructure priority. It’s crazy that planning for capital projects is squeezed into a five-year time frame. Something the nuclear industry, for example, would consider laughable. Reservoirs take years to plan, years to build and a long time to fill. We need long term investment planning if we are to be in anyway serious about resolving the challenges posed by declining water quality, climate change and population growth.

Here are some much needed reforms the new Environment Secretary should bring in immediately:

- The National Infrastructure Commission should be instructed to set out the funding needed to:

- adapt to climate change

- restore infrastructure to a decent standard (e.g. by setting a target to match European average replacement rates by 2030)

- eliminate ecological harm

- eliminate all serious pollution incidents.

OFWAT (or its successor) should be required to deliver consent to match that level of funding or explain to Parliament why it hasn’t.

- The new government should replace the clunky and little heeded Strategic Policy Statement for Water – currently the only way ministers can seek to influence the ‘independent’ regulator – with an Outcomes Direction to force them to take decisions in line with the priorities above.

While a new Water Act is necessary in the next Parliament these immediate measures would not require legislation. The current Water Industry Act just says that government should provide high-level guidance to the regulator. The problem is that it doesn’t.

8) New legislation to reduce abstraction and improve water security

With 85% of the world’s chalkstreams located in England, our stewardship of these precious assets is little short of shameful. These globally recognised, iconic ecosystems should be exemplars of a pristine aquatic environment. Instead, some are now used as open sewers and others are sucked dry through over abstraction. The Hertfordshire chalkstreams such as the Rib, Beane, and Ver have been reduced to a shadow of their former selves and now are often completely dewatered in stretches that were once home to a thriving population of brown trout and coarse fish. Water companies like Affinity find it easier and cheaper to suck the chalk aquifers dry rather than invest in the storage of winter rainfall.

A basic tenet of any water policy must be to collect surplus in times of plenty to guard against economic and environmental damage in times of scarcity. A new Water Act must enshrine this principle into law.

It should also do the following:

- Streamline the planning process for water resources projects so that small projects, including nature-based solutions, that interlink are approved as one project.

- Amend Development Consent Order legislation so that non-potable water schemes are eligible. This is crucial for speeding up delivery of water transfers in and between regions.

- Set a clear target for drought resilience standards as legal minimums (currently they are advisory).

- Reform building regulations to ensure proper water efficient homes (including appliance labelling and minimum efficiency standards).

- End the developers automatic right to connect into the local sewerage system if it lacks sufficient capacity to treat the effluent to standard. Force developers to pay for local upgrades required by their proposals.

A reduction in abstraction is vital to stop rivers running dry

9) Re-use wastewater

The UK is well behind other countries in using wastewater sensibly. For example, in Spain it’s a requirement to use treated wastewater on golf courses rather than abstracting fresh drinking water from the public supply.

We need to quickly follow what is already happening in Europe by using treated wastewater for agricultural irrigation and businesses. This would reduce demand and abstraction and could make a significant difference to river health thereby improving the environment for invertebrates and fish.

10) Overhaul the Environmental Permitting Regime

If having a combined rainwater and foul water sewerage system complete with storm overflows delivers ‘pollution by design’ the anomalies in the current permitting system create ‘pollution by permission’. The whole system needs a complete overhaul focusing on the health of the rivers and seas rather than treating them as dumping grounds of last resort when the system fails or trigger points are reached.

A particularly absurd anomaly sees water companies measured on what they keep in the pipe not what spills out of it. And the counting of storm overflow spills makes little sense as currently a five-minute spill is counted the same as one that lasts 12 hours. We need to move to assessed volumetric measures. It’s the volume of shit that needs counting, not the length of time a pipe might be dribbling.

It is also ridiculous that pipes at the same sewage treatment site are individually permitted rather than permitting all the combined output with an incentive to maximise the treated flow.

11) Worry more about major system failure

The headline figures on sewage pollution are primarily around storm overflows, but just wait until the rising mains start crumbling as is already happening in the Thames Water region. That’s when we get total wipe out – when a problem becomes an environmental catastrophe. By 2050, in many of our water companies a majority of their rising mains will be over 100 years old and well past their sell by dates. In a few cases we are still relying on the brilliance of Victorian engineers to keep untreated sewage out of the rivers. This is clearly not sustainable.

Of course, storm discharges are unacceptable, they are horrible and stink, but do a lot less damage than a fractured rising main sewer. Investment priorities need to be focused on reducing the most harm and this should include getting ammonia and phosphorus levels down in small streams in dry weather where the harm caused to fish and invertebrates is acute.

12) Embrace citizen science and involve stakeholders in the management of rivers

Anglers and local river groups invest millions of hours of volunteer time every year into the maintenance and improvement of water environments by clearing litter, restoring habitats and monitoring and fighting pollution. They see what is happening and are often ‘the canaries in the coal mine’. Currently the EA does nothing about discharges from septic tanks or from the growing army of live-aboard boaters. Local intelligence can help plug these gaps.

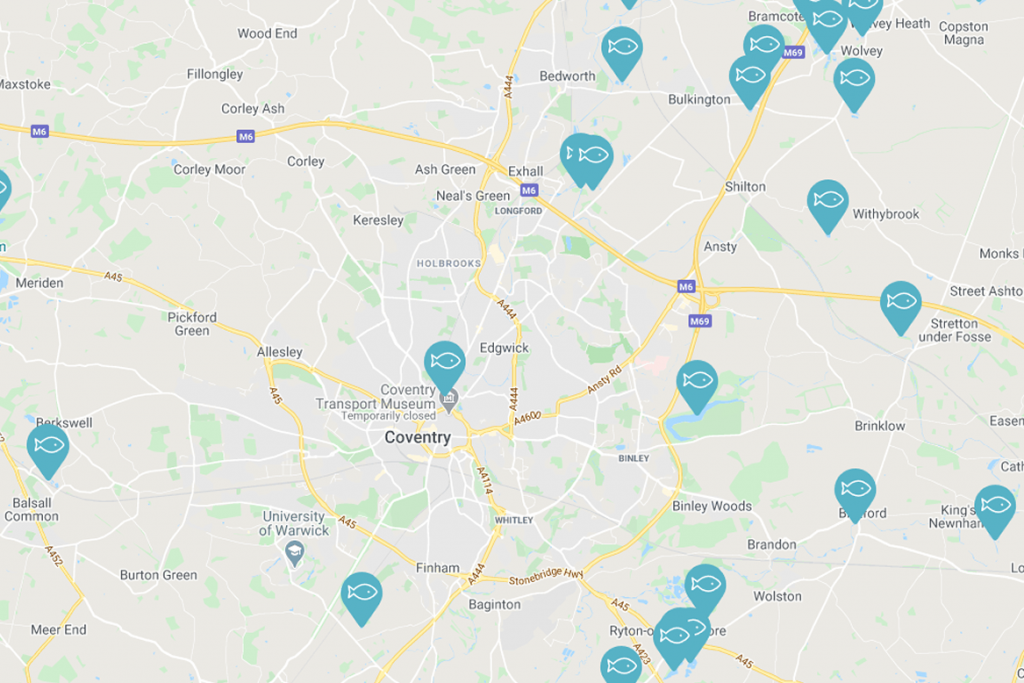

In 2022, in response to record levels of sewage discharges and the continued failure of the Environment Agency to properly monitor the threats to our rivers, the Angling Trust established a national Water Quality Monitoring Network of citizen volunteers to collect and analyse water samples in their areas. It has now engaged over 784 anglers from 278 clubs operating on 202 rivers across 68 catchments collecting around 5,600 individual samples. The results are alarming with 44% of samples exceeding recommended phosphate and nitrate levels, 200 incidents of algae blooms and 300 pollution incidents observed.

Citizen science clearly has a big role to play as we need much better data to make proper decisions but currently the EA won’t accept their results. This is absurd and we need the government to intervene and ensure a role for citizen volunteers alongside an accreditation scheme with independent verification.

Our Water Quality Monitoring Network shows citizen science has a big role to play in river management

Summary

The privatisation of our water industry has been a disaster and I doubt if any of the politicians likely to be in the hot seats in DEFRA have any real comprehension of the extent and scale of the problems they are about to inherit. But let’s not get too starry eyed about the record of the sector in public ownership for there really was no ‘golden era’ when the rivers flowed bright and clear and the taps kept running. In the 1950’s the tidal Thames in London was declared ‘biologically dead’ and further upstream around Staines, where I grew up, there were signs advising us not to bathe in its polluted waters.

There are now many rivers and streams that have been brought back from the brink primarily thanks to European legislation like the Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive, as well as tougher domestic controls. But rules and regulation require properly funded and empowered regulators with a clear sense of purpose that put the environment first. They also require an industry that is accountable and an infrastructure that it fit for purpose rather than the ‘creaking and leaking’ timebomb that is about to land on the desk of the new Secretary of State for the Environment.

By all means, play around with different ownership models that deliver proper accountability for this most vital of our public assets. But please, please don’t forget to fix the pipes.

Martin Salter,

Angling Trust Head of Policy

Download a copy of our Angling Manifesto – Vote for a Fishing Future

You might also like

Reel Education is continuing to grow from strength to…

Government Announces Proposed Ban on Bottom Trawling in 41…

Angling Trust Presses Water Commission to Go Faster and…

VIDEO: Alice and her 3 boys have a day…

Recovery Rods help boost mental health and wellbeing by…

Teddy is hooked! – back for more fishing and…

Thank you to all our volunteers – you do…

Get Fishing Fund – Funded Project: HACRO were visited…

New Horizons had an amazing day taking part in…

Get Fishing Fund – Funded Project Blog: Steve Clamp…

Somersham Angling Club hosted some fabulous Get Fishing events…

BLOG: Jack’s Back! What’s been happening in my East…

Reel Education is continuing to grow from strength to…

Government Announces Proposed Ban on Bottom Trawling in 41…

Angling Trust Presses Water Commission to Go Faster and…

VIDEO: Alice and her 3 boys have a day…

Recovery Rods help boost mental health and wellbeing by…

Teddy is hooked! – back for more fishing and…

Thank you to all our volunteers – you do…

Get Fishing Fund – Funded Project: HACRO were visited…

New Horizons had an amazing day taking part in…

Get Fishing Fund – Funded Project Blog: Steve Clamp…

Somersham Angling Club hosted some fabulous Get Fishing events…

BLOG: Jack’s Back! What’s been happening in my East…

Reel Education is continuing to grow from strength to…

Government Announces Proposed Ban on Bottom Trawling in 41…

Angling Trust Presses Water Commission to Go Faster and…

VIDEO: Alice and her 3 boys have a day…

Recovery Rods help boost mental health and wellbeing by…

Teddy is hooked! – back for more fishing and…

Thank you to all our volunteers – you do…

Get Fishing Fund – Funded Project: HACRO were visited…

New Horizons had an amazing day taking part in…

Get Fishing Fund – Funded Project Blog: Steve Clamp…

Somersham Angling Club hosted some fabulous Get Fishing events…