Lines On The Water

Making Grayling

How modern science and a feather are helping to support grayling stocks across the country.

Last year, Lines On The Water told the story of a grayling project which aims to safeguard and strengthen natural stocks in identified waters.

The story reflected two Yorkshire angling clubs which support the project with a ‘grayling day’ capture event and told how those fish are then transported to the Environment Agency’s National Fish Farm at Calverton in Nottinghamshire. Once they’re there, a controlled spawning process takes place before the donor fish and resultant brood fish are released back into the waterways.

But how does the science actually come together once the ‘materials’ are at Calverton? This year, we’ve taken a close look at the skilled methods which are helping to ensure a future for ‘The Lady Of The Stream’.

“Our responsibility to the Trout & Grayling Strategy is to make sure that the brood fish we collect and their progeny go back to the same catchment so they keep their genetic integrity,” says Dan Clark from Calverton Fish Farm. “The brood stock is always taken from stretches that have grayling in abundance and their offspring are returned into areas of the same catchment where grayling stocks are struggling. That may be because of a pollution issue or predation. We work with angling clubs, usually identified by the local fisheries officer to organise the collection of the donor fish.”

Always a treat.

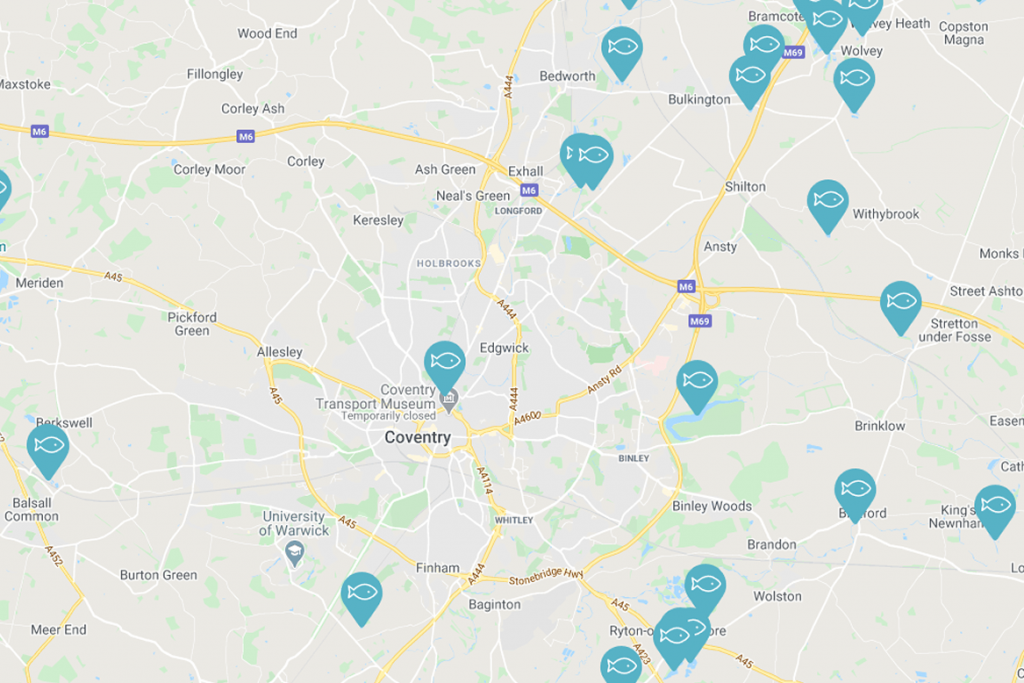

Calverton works with four different catchment areas and this year they focused on three of them: The Kennet in the South, The Wharf in the North and the Derbyshire Derwent in the Midlands. In the case of the Derwent, the brood fish were taken from a private stretch of the Derbyshire Wye – a tributary of the Derwent – at Haddon Hall. While the brood fish are returned to their ‘home’ water, the offspring are used in identified areas of the wider catchment which means greater numbers of grayling are more accessible on public waters.

As reflected in last year’s story, rod and line is always used to catch the brood fish as it’s the least stressful method of capture. Other methods have been tested and analysed in the past but traditional angling practice provides the best results when it comes to minimising stress and maximising offspring. So, on the appointed day, the anglers from the identified clubs catch the fish and hand them over to the scientists. But what happens then?

“The fish are put into specially designed vehicles that have oxygenated tanks and fresh bore-hole water,” says Dan.

“Each tank has its own alarm system, so we know the fish have a good quality of water during transportation and we add three substances taken from the salmon industry and designed for delicate species to keep the fish calm and to minimise risk from parasites and potentially harmful diseases and bacteria.”

In the northern catchment area, the course of events for this year’s brood stock reflects a process that is planned to specifically minimise the period of captivity for the donor fish.

Day 1 – Collected on the Wharf

Day 2 – Sexed and primed (small dose of hormone given to encourage fish into a breeding pattern)

Day 6 – Second hormone known as a ‘Resolvent Dose’ to encourage fish to become sexually active.

After another three or four days, the fish are left in a controlled environment before they are checked again. At this point, the females are transferred into an anaesthetised spawning tank. This allows them to be handled and inspected safely. Handlers know that ovulation is occurring when, after gentle manipulation of a belly swollen by the previous hormone treatment, eggs are freely recovered.

Expressing the eggs.

“Imagine the eggs as a bunch of grapes inside the female which are connected with branch-like attachments,” says Dan. “When the fish are ready, these break down so the eggs are loose and come out freely. That’s when we know they are ovulating.

“The eggs must be kept dry because when the egg touches water it instantly begins to swell up which closes the micropyle that the milt swims into. You’ve got literally a couple of seconds before all doors are closed. The eggs are expressed into a bowl and then we immediately add the milt.”

When it comes to the males, the team identifies at least two males per female to insure against potential infertility. They then anaesthetise the fish and extract milt with an adapted syringe. For both eggs and milt, time is of the essence.

Ready.

“At the next stage, everything is mixed together and we add a fertilise solution and leave everything for about an hour to ensure optimum fertilisation.”

When mentioned in isolation, the ‘mixing’ process sounds somewhat robust for such an occasion but at Calverton they’ve retained a traditional approach.

“We stir the eggs and the milt with a feather. You’d be hard-pressed to find something that’s as strong yet gentle at the same time, so a feather is perfect.”

After the resting period, the eggs are laid out into trays which are then put into troughs. The eggs are roughly 3mm in diameter and each tray will house around 3,500 eggs. With five trays to a trough, the returns on the investment from a tankful of donor fish is potentially immense.

Clean bore-hole water flows through the troughs at a constant 10 degrees centigrade with a tiny level of disinfectant trickling into the water to keep any bacteria at bay during this critical time. The eggs are then left until they hatch, which for grayling is a process that takes approximately two weeks.

At the hatching point, cleanliness remains paramount because the hatchlings are extremely vulnerable. A yolk sac supplies an instant food source for approximately five-to-seven days.

“They swim a little, but essentially, they sit on the bottom of the tank because they haven’t filled their swim bladder,” says Dan. “This happens when they’ve eaten their yolk sac. They take a gulp of air and start swimming around the tank.”

At this stage, the new kids on the block are given their first feed which is always Artemia, otherwise known as Brine shrimp. A very fine, pelleted food is added as the fish continue to grow but the process remains precise and is constantly updated by recent breakthroughs.

“We’ve learned in the last couple of years that the grayling has a very small liver compared to other coarse fish, so we have to feed them a low-fat, low-oil diet. It’s made a big difference to our growth and survival rates.

“With the methods that we use, we would expect a low mortality rate at this point. From fertilisation, we expect about an 80% survival rate. But as much as we have amazing facilities at Calverton, we can’t replicate Mother Nature. So it’s important that we get them out to natural waters as early as possible but at the same time they have to be strong enough to have a chance of survival.”

Over a period of around six-weeks from hatch, the fish will grow and become identifiable as grayling. At a point around release time, they will eat pretty much anything and the constant water flow through the tanks will have built up important muscle sets as the fish learn to swim against a current. By now, ‘Mum and Dad’ have long since been returned to their capture site. After just a week at the farm, their jobs are done and the ‘kids’ are left fending for themselves.

A constant process to ensure cleanliness and a six-times-a-day, seven-days-a-week feeding regime means this is a full-on period for Calverton’s staff. At the point of release, the fish may be ready to go, but they’re still too fragile to handle.

Release day.

Dan says: “Release is a weird balance. On the one hand you’d like to put loads back into the river and hope they survive, on the other, you’d keep them at the farm and make them as strong as possible. But both have their sets of risk.

“In the wild, they’re obviously part of the food chain so anything from other fish to kingfishers will give them a go. You’ve got trout in a lot of the waters that grayling live in so the whole process is against them. But obviously they survive because the 2/3lb fish you see in the magazines or on social media have all been through this process of development. However hard we try, we can’t imitate nature and if we held them at our farm fish for any longer than we do, I think our input would become detrimental.”

Nearly there.

Once in the wild, survival rates are estimated to hover around a rate of 2% although such a stark figure is balanced by the number of eggs produced at the outset. A female fish can produce anything between 3,500 and 30,000 eggs per kilo but even so, the number reaching adulthood is minuscule and illustrates the importance of the work Calverton does.

When set against nature’s alternative, it does seem that Calverton offers newly hatched grayling the best head start they could have. There is never a suggestion that this is a process that can replace natural pro-creation, merely that it supplements it in the areas that research identifies as requiring it.

Over the course of a year, Calverton will perform this process for eight other species – albeit in a manner that accounts for individual behaviours. These are dace, roach, rudd, crucian carp, bream, barbel chub and tench.

Home.

The final word is Dan’s: “We can never quantify the difference the process makes but from the feedback we receive, we know it is working. You’d never get as many fertilised eggs surviving in a flowing river and the chances of them succumbing at the hatchery are fantastically lower than they are in the wild.”

You might also like

We want a water industry fit for purpose

Another year of anglers’ data reveals another year of…

Get Fishing Fund – Funded Project: ‘Summerhayes Junior Angling…

Will the UK-EU Fisheries Deal Deliver for Sustainability and…

The smile says it all! Kayson is hooked! –…

Our Man with a Mullet! Dean Asplin, enjoys a…

Underdog Crew hosts top draw fishing events with Hintlesham…

NEW BLOG: Fishing helped my Peaceful Place members with…

Minister’s Visit Highlights Collaborative Action on Pollack Conservation

Angling Trust calls for radical reforms to end sewage…

Have Your Say: Shape the Future of Black Bream…

NEW BLOG: Get Fishing Award event for North Cambridge…

We want a water industry fit for purpose

Another year of anglers’ data reveals another year of…

Get Fishing Fund – Funded Project: ‘Summerhayes Junior Angling…

Will the UK-EU Fisheries Deal Deliver for Sustainability and…

The smile says it all! Kayson is hooked! –…

Our Man with a Mullet! Dean Asplin, enjoys a…

Underdog Crew hosts top draw fishing events with Hintlesham…

NEW BLOG: Fishing helped my Peaceful Place members with…

Minister’s Visit Highlights Collaborative Action on Pollack Conservation

Angling Trust calls for radical reforms to end sewage…

Have Your Say: Shape the Future of Black Bream…

NEW BLOG: Get Fishing Award event for North Cambridge…

We want a water industry fit for purpose

Another year of anglers’ data reveals another year of…

Get Fishing Fund – Funded Project: ‘Summerhayes Junior Angling…

Will the UK-EU Fisheries Deal Deliver for Sustainability and…

The smile says it all! Kayson is hooked! –…

Our Man with a Mullet! Dean Asplin, enjoys a…

Underdog Crew hosts top draw fishing events with Hintlesham…

NEW BLOG: Fishing helped my Peaceful Place members with…

Minister’s Visit Highlights Collaborative Action on Pollack Conservation

Angling Trust calls for radical reforms to end sewage…

Have Your Say: Shape the Future of Black Bream…