Seals in Freshwater

Seals may spend several days at sea and travel up to 50 kilometres in search of feeding grounds but will also swim some distance upstream into freshwater in large rivers. When not actively feeding, seals will haul themselves out of the water and onto a preferred resting site. Common seals tend to hug the coastline, usually not venturing more than 20 kilometres offshore and frequently choose to congregate in harbours, which refers to their other name of ‘harbour seal’.

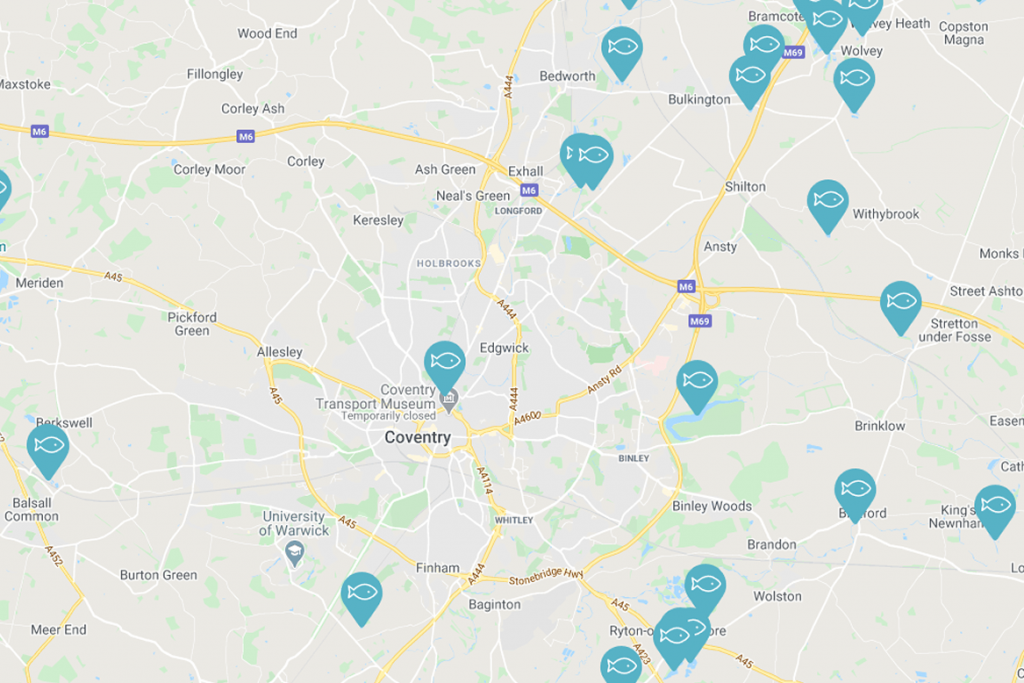

Seals are known to frequent a number of the UK’s rivers including for example the Tees, Yorkshire Ouse, Severn and Mersey. During 2013 a common seal is thought to have swum more than 50 miles (80km) along a flooded river into a lake at Fen Drayton Lakes Reserve, in Swavesey, Cambridgeshire. The specific reason why seals choose to swim inland is uncertain, but suggestions have been made that they are simply following a food source, e.g. a salmon or sea trout ‘run’ at a particular time of year and then become disorientated. The period of time they remain in freshwater varies from days, to several months in some cases.

It is these longer visits that sometimes draw them into conflict with freshwater anglers and the potential impact they may be having on the fish stocks. Questions are often raised as to what can be legally done to resolve the issue. More often than not the seal will naturally return to sea within a few days. Alternative measures often discussed include the live trapping, hooping, or netting of the specific seal, lethal shooting and the use of acoustic deterrents devices (ADDs).

Following the floods at the end of 2012 there were sightings of a seal in Worcester, Bewdley and at the marina in Stourport-on-Severn, about 50 miles from the sea. Having sought the advice from a number of wildlife conservation groups, including the British Divers Marine Life Rescue, the intention was to pursue the option of live capture. However, the actual practicalities ultimately proved too problematical and anglers had to wait until the seal returned to sea.

Lethal control using a qualified marksman under licence would undoubtedly result in a strong expression of public disapproval and anger. Once again there would be logistical issues to consider should that option be considered, not least the safety requirements of using a rifle in this environment over water. Before any such licence could be considered all reasonable and practical non-lethal deterrents would have to have been considered. One such option would be the use of acoustic deterrents.

Marine Scotland has already supported the development of a new acoustic deterrent device that can deter seals without disturbing cetaceans (whales, dolphins etc.) It is now supporting field testing of this device with a view to potential future deployment in fisheries and/or fish farms.

In England, the Canal & Rivers Trust have trialled the use of acoustic deterrents at the Tees Barrage where seals not only predate on salmon waiting to pass through the barrage but also use the navigation lock to access upstream to highly valued coarse angling waters. Attempts are continuing to find a solution to this.

A number of wildlife organisations are involved in the rescue of injured seals or seal pups that have been abandoned. These seals often end up in the care of rescue centres for rehabilitation before release back to the wild. The Angling Trust supports such initiatives, but we have concerns that in some cases the release points chosen are in the tidal zones of rivers, increasing the risk seals will move into the freshwater environment rather than back in to the marine environment. There have been documented instances where this has resulted in an impact on freshwater fish species in terms of behavioural change, the movement of fish species away from their natural in-river habitats, and the loss of local populations through predation. Freshwater fish species are not accustomed to evading seal predation resulting in a far higher level of loss that would be experience through their natural predators.

To address the problem of over predation of freshwater fish species, we urge organisations involved in seal rescues to ensure subsequent releases are undertaken as close as practicably possible to the site where the seals were originally rescued on the coast. This is best animal welfare practice for other released animals, for example otters.