Marine

Skippers & Anglers Urge Fisheries Minister Caution on Spurdog

The Angling Trust are proud to support the Pat Smith Database through Shark Hub UK to campaign against the current measures of the reopened commercial spurdog fishery. Both the Angling Trust and the Pat Smith Database have written to the Fisheries Minister urging caution as the commercial sector lobbies for an increase to the current 100cm slot size.

The spurdog, also known as the spiny dogfish, is a fascinating and enigmatic species that once thrived in the waters surrounding the United Kingdom. The UK government gave the green light to reopen the commercial fishery for spurdog in April 2023 with a combined total allowable catch of 7,606 tonnes for 2023 following ICES advice that the stock is showing signs of recovery. In the interests of conservation, the UK agreed with the EU on a “precautionary” slot size of 100cm – meaning any females over 100cm cannot be landed and must be released – designed to protect mature females, but concerned anglers and skippers argue this isn’t enough to conserve the species and are already worried about the stock’s sustainability. While female spurdogs can reach lengths of up to 120cm, on average they reach around 100cm with 50% of females being mature between 74 – 83cm.

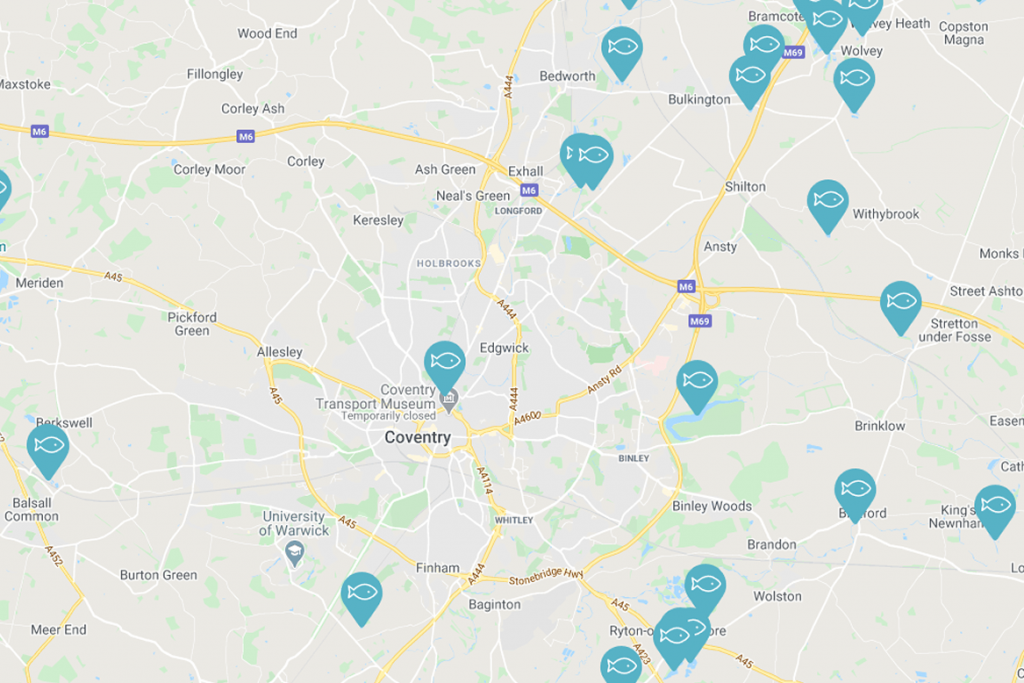

With anglers and skippers up and down the coastline noticing the disappearance of spurdogs from areas where they were once abundant prior to the commercial fishery reopening, fears are growing about the population’s future and the angling and charter boat businesses that depend on catching and releasing the species. There are also concerns about other small sharks like bull huss, smoothhound and tope linked with bycatch from the reopened commercial spurdog fishery.

The Plight of the Spurdog

Spurdog (Squalus acanthias) is a slow-growing species, taking many years to reach maturity. It can take up to 15 years for a female spurdog to reproduce for the first time, and males can take around 11 years. This late maturity makes the spurdog particularly vulnerable to population pressures. Some individuals are known to live up to 75 years. Spurdog also sexually segregate, i.e. males and females are separate apart from when they are mating, which makes them especially vulnerable to overfishing. In addition to their slow growth rate, spurdogs have low fecundity, meaning they produce a small number of offspring compared to other fish species. Female spurdogs typically give birth to around 2 – 15 pups every two years. Between 18 – 24 months long, they have one of the longest gestation periods recorded for a vertebrate. This reproductive strategy, combined with their late maturity, further hampers their ability to replenish their population in the face of increasing fishing pressure.

The Impact of Overfishing

Historically, spurdogs were plentiful in our waters and were heavily targeted by both commercial fishers and anglers. Unfortunately, this relentless fishing pressure decimated their numbers in the UK waters throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Due to intense overfishing, the Northeast Atlantic spurdog stock is among the most depleted spurdog populations in the world and was near collapse. In the interests of protecting the remaining population, spurdog was listed on the prohibited species list in 2010 with a 0 Total Allowable Catch (TAC) in place. From the verge of collapse, spurdog has shown signs of recovery since the 0 TAC was implemented, but the rush to reopen the commercial fishery makes them vulnerable to repeating the mistakes of the past.

A Call for Conservation

In recent years, anglers and skippers have observed on the ground the recovery of spurdog leading to collaborations with citizen science groups like Spurwatch UK. You can learn more about Spurwatch UK in our Love Fishing, Love Nature film.

Defra’s hurry to take spurdog off the prohibited species list and reopen a commercial fishery at the first sign of recovery is a perfect example of boom-and-bust fisheries management. Historically, their meat was prepared for human consumption, their liver oil (squalene) in cosmetics and their fins traded on the international fin market. Nowadays spurdog has little commercial value and is mostly used for pot bait rather than filling a food security need. In our view, this is not the best way to manage this species and ignores the value of sustainable fisheries across coastal communities and the wider marine environment.

On the international stage, the UK is proud to call itself a world leader in shark conservation with the recent landmark Shark Fin Act, but at home, it seems the UK government is unbothered about its own shark species.

The UK Government has promised “world-class fisheries” upon our departure from the European Union and has recognised recreational fisheries as a legitimate stakeholder in UK fisheries management. It is simply not enough for the overarching goal of fisheries management to be recovering populations back to the status quo. We need to be more ambitious for thriving seas and move toward ecosystem-based management. Skippers and anglers across the country are urging the Fisheries Minister to take note of their concerns both for the stock’s health and for their livelihoods.

We now need to see action from the UK Government to support its vision for “world-class fisheries” and its commitment to the recreational sector.

You might also like

ENGLAND WIN SILVER, RINGER TAKES GOLD, AND MASTERS FINISH…

‘Lady of the Stream’ photographer Amber Banks Brumby captures…

ANGLING TRUST APPOINT NEW MANAGER FOR ENGLAND DISABLED TEAM

SILVER FOR ENGLAND IN MASTERS FEEDER WORLD CHAMPS

MANAGER NAMED FOR NEW ENGLAND U22 CARP TEAM

Anglers Views Needed on Southern IFCA Shore Gathering Byelaw

Angling Improvement Fund now open for projects to control…

Londoner selected for Angling Trust’s short film YouTube series

📷 NEW PHOTOS: Get Fishing event at Portishead Marina…

ENGLAND KAYAK TEAM WIN SILVER IN CLOSE WORLD CHAMPS

The Fisheries Improvement Programme – Supporting Club Development