Seals around the British Isles

Common and Grey Seals

There are two types of seal found around the British Isles – the common (harbour) seal and the grey seal. Both are relatively common and in certain areas are seeing their numbers increase – an issue which some say is responsible for reducing fish stocks and leads to concerns from sea and freshwater anglers alike. According to the Mammal Society the common seal is in fact less common in British waters than the grey seal, at about 55,000 compared with around 120,000 grey seals, but around Ireland the two species are more equally represented: about 3,000 common seals and 4,000 grey seals. Other species of seals, such as the harp seal, hooded seal and ringed seal are very occasional visitors to the British Isles, and any sightings of these species are extremely rare.

Common Seal

Credit: Adam Cuerden (Wiki Commons)

- Scientific name: Phoca vitulina

- Also known as: Harbour Seal

- Size: Generally adult males weigh about 85kg and measure about 145cm in length (but have been known to reach 135kg and 185cm). Females weigh about 75kg and are about 135cm long, not much smaller than the males, in fact it is very difficult to tell the males from females.

- International Union for Conservation of Nature status:

– Global: LC (Least Concern)

– Europe: LC (Least Concern) - Distribution: Common around the British Isles and the colder waters of most of Northern Europe. Also common in North American waters with smaller populations elsewhere in the world.

- Feeds on: Mostly fish and squid with all species being taken. May also consume other sources of food which become available such as crabs, lobsters and even marine birds.

- Description: Large powerful fat body with relatively small flippers. Relatively small rounded head with large eyes and nostrils which are close together. Mouth is full of small but sharp teeth. Colour can vary greatly from dark brown/black to light grey. Speckled/spotted colour is present across back and body.

Common seals are found all around the coastline of the British Isles with the highest populations around Scotland and along the eastern coast of England. They are also found throughout the colder waters of Northern Europe. They are non-migratory animals which spend their lives close to the shore, rarely venturing more than a few miles out to sea, but can also be found in rivers.

Common seals live in large groups and can make their home on a variety of different shorelines ranging from sandy beaches and sandbanks to fairly rocky and rugged coasts. However, common seals spend the majority of their time in the water. They are capable of diving to depths of several hundred metres and can remain submerged for over half an hour.

Credit: Adam Cuerden (Wiki Commons)

Common seals are unfussy predators which will hunt and eat any type of fish which is available with pelagic (mid-water) species such as mackerel being taken as well as demersal (bottom-dwelling) species such as cod, haddock and plaice and migratory fish such as salmon all being preyed upon. They will also feed on other food sources which present themselves with common seals being known to eat squid, cuttlefish, crabs, lobsters and even marine birds at times. When found in rivers they will also feed on any freshwater fish present.

Females give birth in the summer months after a nine-month gestation period. While the young have an innate ability to swim they are still cared for by their mothers for around two months and rapidly put on weight due to the fatty milk the mother produces. All common seals go through a moulting process after breeding and must spend a longer proportion of time on land during this time.

Grey Seal

- Scientific name: Halichoerus grypus

- Also known as: Horsehead Seal and Atlantic Grey Seal

- Size: There are significant size differences between adult males and females. Generally adult males weigh up to 300kg and c.250cm long (but have been known to reach 360kg and 300cm), while adult females weigh up to 180kg and are about 180cm long.

- International Union for Conservation of Nature status:

– Global: LC (Least Concern)

– Europe: LC (Least Concern) - Distribution: Found mostly around the north of the British Isles with the UK population representing about 40% of the world population and 95% of the EU population. Also distributed throughout Scandinavian and northern European waters with other populations in North America and an isolated population present in the Baltic Sea.

- Feeds on: Fish and squid along with crustaceans and pretty much any other sources of food which are present.

- : Colouration differs between the sexes: males are dark grey, brown and black with some lighter blotches over the fur, whilst females are generally light grey with darker blotches. Grey seals have a blubbery but powerful body, a longish snout with large eyes and nostrils which are spaced apart. Fully grown males also have thick rolls of flesh around the neck and chest areas and a concave ‘Roman’ nose.

Credit: Mark Garratt (Wiki Commons)

The grey seal is a species which is found around the colder northern regions of the British Isles. There are notable breeding colonies in a number of places around the UK such as off the coast of Northumberland, Lincolnshire and the Orkney Islands. The grey seal is a species which grows to a much larger size than the common seal, with males being substantially larger than females. The main difference between the two species of seal is that the grey seal has a much longer snout than the common seal, and the nostrils of the grey seal are spaced far apart, while they are close together in the common seal.

Like the common seal, the grey seal spends a lot of time in the water where they hunt for all manner of fish species but will also take squid, crustaceans and other sources of food which present themselves. They live in large colonies which can consist of thousands of individual seals, with seals hauling-out (leaving the water) to rest and bask after they have been hunting. Females give birth in late summer/early autumn and care for their offspring for a number of weeks until the soft white fur of the young has been replaced by the adult’s waterproof fur. Numbers of grey seals are on the rise across the world, leading to concern in some quarters over the impact this will have on fish stocks.

Seals in Freshwater

Seals may spend several days at sea and travel up to 50 kilometres in search of feeding grounds but will also swim some distance upstream into freshwater in large rivers. When not actively feeding, seals will haul themselves out of the water and onto a preferred resting site. Common seals tend to hug the coastline, usually not venturing more than 20 kilometres offshore and frequently choose to congregate in harbours, which refers to their other name of ‘harbour seal’.

Seals are known to frequent a number of the UK’s rivers including for example the Tees, Yorkshire Ouse, Severn and Mersey. During 2013 a common seal is thought to have swum more than 50 miles (80km) along a flooded river into a lake at Fen Drayton Lakes Reserve, in Swavesey, Cambridgeshire. The specific reason why seals choose to swim inland is uncertain, but suggestions have been made that they are simply following a food source, e.g. a salmon or sea trout ‘run’ at a particular time of year and then become disorientated. The period of time they remain in freshwater varies from days, to several months in some cases.

It is these longer visits that sometimes draw them into conflict with freshwater anglers and the potential impact they may be having on the fish stocks. Questions are often raised as to what can be legally done to resolve the issue. More often than not the seal will naturally return to sea within a few days. Alternative measures often discussed include the live trapping or netting of the specific seal, lethal shooting and the use of acoustic deterrents (scrammers).

Following the floods at the end of 2012 there were sightings of a seal in Worcester, Bewdley and at the marina in Stourport-on-Severn, about 50 miles from the sea. Having sought the advice from a number of wildlife conservation groups, including the British Divers Marine Life Rescue, the intention was to pursue the option of live capture. However, the actual practicalities ultimately proved too problematical and anglers had to wait until the seal returned to sea.

Lethal control using a qualified marksman under licence would undoubtedly result in a strong expression of public disapproval and anger. Once again there would be logistical issues to consider should that option be considered, not least the safety requirements of using a rifle in this environment over water. Before any such licence could be considered all reasonable and practical non-lethal deterrents would have to have been considered. One such option would be the use of acoustic deterrents.

Marine Scotland has already supported the development of a new acoustic deterrent device that can deter seals without disturbing cetaceans (whales, dolphins etc.) It is now supporting field testing of this device with a view to potential future deployment in fisheries and/or fish farms.

In England, the Canal & Rivers Trust have trialled the use of acoustic deterrents at the Tees Barrage where seals not only predate on salmon waiting to pass through the barrage but also use the navigation lock to access upstream to highly valued coarse angling waters. Attempts are continuing to find a solution to this.

A number of wildlife organisations are involved in the rescue of injured seals or seal pups that have been abandoned. These seals often end up in the care of rescue centres for rehabilitation before release back to the wild. The Angling Trust supports such initiatives, but we have concerns that in some cases the release points chosen are in the tidal zones of rivers, increasing the risk seals will move in to the freshwater environment rather than back in to the marine environment. There have been documented instances where this has resulted in an impact on freshwater fish species in terms of behavioural change, the movement of fish species away from their natural in-river habitats, and the loss of local populations through predation. Freshwater fish species are not accustomed to evading seal predation resulting in a far higher level of loss that would be experience through their natural predators.

To address the problem of over predation of freshwater fish species, we urge organisations involved in seal rescues to ensure subsequent releases are undertaken as close as practicably possible to the site where the seals were originally rescued on the coast. This is best animal welfare practice for other released animals, for example otters.

Hunting and Culling Seals

Humans have hunted seals for thousands of years. There is evidence that ringed seals (Pusa hispida) have been hunted in Canada for over 4,000 years. Seals were harvested intensively throughout Canada, Alaska and Europe throughout the 1700s. In the 1800s the development of steam-powered ships which had the ability to break through ice allowed the hunting of seals to massively expand and 1872 saw almost 750,000 seals killed in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and Newfoundland area alone.

Today, seals are still hunted commercially by six countries: Greenland, Iceland, Norway, Canada, Russia and Namibia (the only Southern Hemisphere country which hunts seals).

The Canadian quota of seals which are killed in the annual seal hunts has been rising in recent years as the value of seal products has gone up. In 2015 the quota was set at almost 500,000 seals with harp seals, hooded seals and grey seals making up the majority of the quota. The Canadian seal hunt is subsidised by the government and environmental campaigning bodies campaign strongly against the actions of the Canadian government and attempt to draw public attention to the hunting of seals. Norway is responsible for killing around 30,000 seals per year and Russia accounts for around 5,000-6,000 seals.

Seals are not hunted in the United Kingdom although licences can be granted to shoot seals if they threaten the stocks of fish farms (see licensing section below).

Seal Legislation & Licensing

The principal piece of UK legislation is the Conservation of Seals Act 1970 which prohibits the killing or taking of seals by certain methods and during close seasons. Both seal species are Annex II species protected under the European Habitats Directive in sites known as Special Areas of Conservation. Seals are protected within these sites from any activity that could impact the favourable conservation status of that population, which could include restrictions on control.

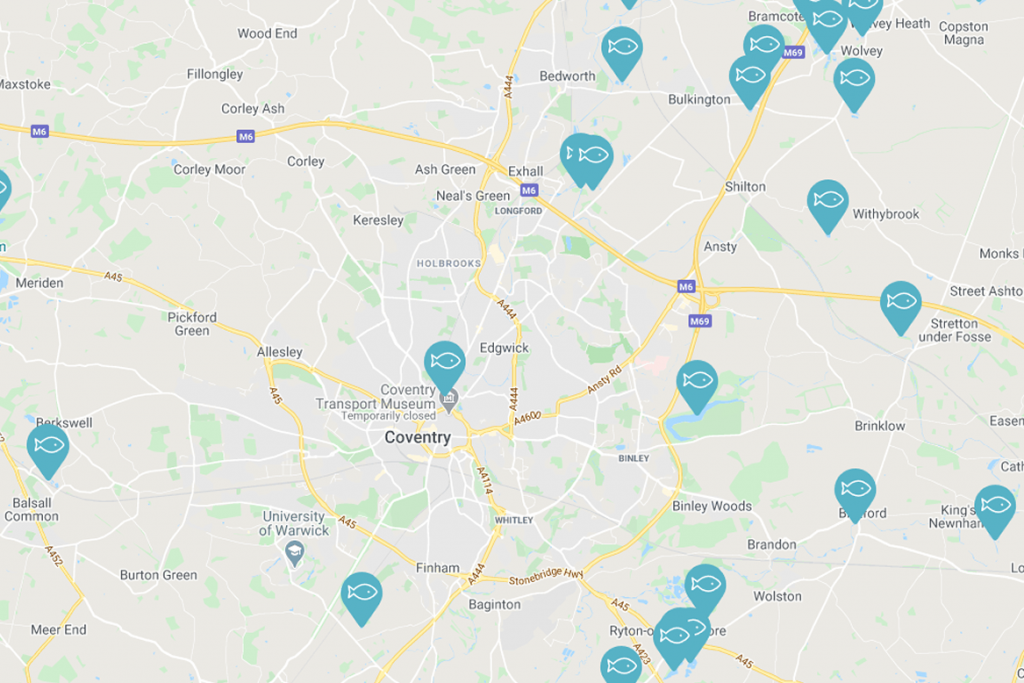

Distribution of SACs/SCIs/cSACs containing species

Common or Harbour Seal Phoca vitulina.

Copyright: Joint Nature Conservation Committee

Distribution of SACs/SCIs/cSACs containing

species Grey Seal Halichoerus grypus.

Copyright: Joint Nature Conservation Committee

Explanation of grades

A: Outstanding examples of the feature in a European context.

B: Excellent examples of the feature, significantly above the threshold for SSSI/ASSI notification but of somewhat lower value than grade A sites.

C: Examples of the feature which are of at least national importance (i.e. usually above the threshold for SSSI/ASSI notification on terrestrial sites) but not significantly above this. These features are not the primary reason for SACs being selected.

D Features of below SSSI quality occurring on SACs These are non-qualifying features (“non-significant presence”), indicated by a letter D, but this is not a formal global grade.

The Conservation of Seals Act 1970 prohibits the following methods of killing or taking seals:

- Use of any poisonous substance

- Use of any firearm other than a minimum specified rifle with specified ammunition

There is a close season for grey seals from 1st September to 31st December, and for common seals from 1st June to 31st August.

- It is an offence to take or kill a seal during the close season

However, the Secretary of State and devolved administrations can extend that protection to the entire year for either or both the above seal species in any area specified in an order.

Both grey and common seals on the east and south-east coast of England (from Berwick to Newhaven) are protected all year from being killed, injured or taken – (Conservation of Seals (England) Order 1999). This includes the counties of Northumberland, Tyne & Wear, Durham, North Yorkshire, East Riding of Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, Norfolk, Suffolk, Essex, Kent and East Sussex, and administrative area of Greater London. It also covers territorial waters next to England that are south of a line drawn from the point on the mainland at 55’48.67N 02’02.0W and next to any of the areas specified above to no further west than a line drawn true south from Newhaven Breakwater Health Light (50’46.5N 00’03.6E).

There are certain exceptions under this legislation, which are not considered offences and for which a licence is not required:

- Taking / attempting to take a disabled seal for the purposes of tending and releasing it.

- Unavoidable killing / injuring as an incidental result of a lawful operation.

- Killing / attempted killing a seal to prevent it causing damage to a fishing net / tackle, or to fish held in the net, if the seal is in the vicinity of the net / tackle. An appropriate firearms licence must be held to act under this defence.

Licences

However, seals are still killed in Britain under licence with several hundred seals killed in Scotland alone by the owners of fish farms in order to protect their stocks.

England & Wales

In England, the Marine Management Organisation (MMO) is responsible for wildlife licence applications and enforcement between the high water mark for this Act and also inter-tidal riverine areas. Natural England is responsible for any wildlife licence applications in other areas (e.g. rivers) but which are unaffected by the tide. Natural Resources Wales (NRW) can grant wildlife licences for specified purposes within Wales.

The appropriate body can grant licences under powers conferred by the Secretary for State for the following purposes (Section 10(1)):

- Scientific or educational purposes (to kill or take, other than by use of strychnine)

- Zoological gardens / collections (to take)

- Prevention of damage to fisheries (to kill or take)

- Reduction of population surplus for management purposes (to kill or take)

- Use of population surplus as a resource (to kill or take)

- Protection of flora or fauna within areas specified in subsection (4)

Licences to prevent damage will be issued only where all three of the following apply:

- Seals are causing, or likely to cause, sufficiently serious damage to justify a licence

- Other non-lethal methods of control have been shown to be ineffective or impractical, e.g. Acoustic Deterrent Devices/Scrammers

- The licensed activity is likely to be successful in solving the problem

Where a licence application proposes the use of methods prohibited under Regulation 43(3) of the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2010 (as amended), the relevant governing body will consider the application under those regulations.

More information is available at:

Scotland

On the 1st February 2011 it became an offence to kill, injure or take a seal at any time of year except to alleviate suffering or where a licence has been issued to do so by Marine Scotland under the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010.

The actual offence of killing, injuring or taking a seal under the Act applies to all seal species throughout Scotland and includes not only its territorial waters and inland waters, but also the land.

The method of killing or taking seals is detailed in the licences issued annually and regular reporting will be required. Licences can be issued to take or kill a seal for the following purposes:

- for scientific research or educational purposes;

- to conserve natural habitats;

- to conserve seals or other wild animals (including wild birds) or wild plants;

- in connection with the introduction of seals, other wild animals (including wild birds) or wild plants to particular areas;

- to protect a zoological or botanical collection;

- to protect the health and welfare of farmed fish;

- to prevent serious damage to fisheries or fish farms;

- to prevent the spread of disease among seals or other animals (including birds) or plants;

- to preserve public health or public safety; or

- for other imperative reasons of overriding public interest, including those of a social or economic nature and beneficial consequences of primary importance for the environment.

Before granting a seal licence the Scottish Ministers must have regard to any information they have about:

- damage which seals have already done to the fishery or fish farm concerned; and the

- effectiveness of non-lethal alternative methods of preventing seal damage to the fishery or fish farm concerned.

More information available here

Frequently asked questions and answers on the implementation of the new seal legislation was produced in 2011. To read them click here

You can contact Marine Scotland at: [email protected]

or by writing to: The Scottish Government, Victoria Quay. Edinburgh, EH6 6QQ.

Sources:

British Sea Fishing

Marine Management Organisation

Natural Resources Wales

Scottish Natural Heritage

Sea Mammal Research Unit